Hockey Hits Are Hurting More

/One painful lesson every National Hockey League rookie learns is to keep your head up when skating through the neutral zone. If you don't, you will not see the 4700 joules of kinetic energy skating at you with bad intentions.

During an October 25th game, Brandon Sutter, rookie center for the Carolina Hurricanes, never saw Doug Weight, veteran center of the New York Islanders, sizing him up for a hit that resulted in a concussion and an overnight stay in the hospital. Hockey purists will say that it was a "clean hit" and Weight was not penalized.

Six days before that incident, the Phoenix Coyotes' Kurt Sauer smashed Andrei Kostitsyn of the Montreal Canadiens into the sideboards. Kostitsyn had to be stretchered off of the ice and missed two weeks of games with his concussion. Sauer skated away unhurt and unpenalized. See video here.

Big hits have always been part of hockey, but the price paid in injuries is on the rise. According to data released last month at the National Academy of Neuropsychology's Sports Concussion Symposium in New York, 759 NHL players have been diagnosed with a concussion since 1997. For the ten seasons studied, that works out to about 76 players per season and 31 concussions per 1,000 hockey games. During the 2006-07 season, that resulted in 760 games missed by those injured players, an increase of 41% from 2005-06. Researchers have found two reasons for the jump in severity, the physics of motion and the ever-expanding hockey player.

Big hits have always been part of hockey, but the price paid in injuries is on the rise. According to data released last month at the National Academy of Neuropsychology's Sports Concussion Symposium in New York, 759 NHL players have been diagnosed with a concussion since 1997. For the ten seasons studied, that works out to about 76 players per season and 31 concussions per 1,000 hockey games. During the 2006-07 season, that resulted in 760 games missed by those injured players, an increase of 41% from 2005-06. Researchers have found two reasons for the jump in severity, the physics of motion and the ever-expanding hockey player.

In his book, The Physics of Hockey, Alain Haché, professor of physics at Canada's University of Moncton, aligns the concepts of energy, momentum and the force of impact to explain the power of mid-ice and board collisions.

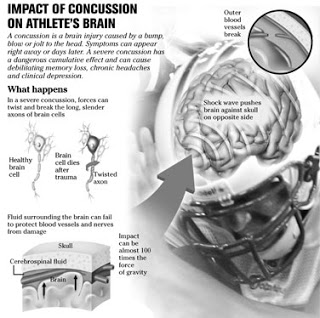

As a player skates from a stop to full speed, his mass accelerates at an increasing velocity. The work his muscles contribute is transferred into kinetic energy which can and will be transferred or dissipated when the player stops, either through heat from the friction of his skates on the ice, or through a transfer of energy to whatever he collides with, either the boards or another player.

The formula for kinetic energy, K = (1/2)mass x velocity2, represents the greater impact that a skater's speed (velocity) has on the energy produced. It is this speed that makes hockey a more dangerous sport than other contact sports, like football, where average player sizes are larger but they are moving at slower speeds (an average of 23 mph for hockey players in full stride compared to about 16 mph for an average running back in the open field).

So, when two players collide, where does all of that kinetic energy go? First, let's look at two billiard balls, with the exact same mass, shape and rigid structure. When two balls collide on the table, we can ignore the mass variable and just look at velocity. If the ball in motion hits another ball that is stationary, then the ball at rest will receive more kinetic energy from the moving ball so that the total energy is conserved. This will send the stationary ball rolling across the table while the first ball almost comes to a stop as it has transferred almost all of its stored energy.

Unfortunately, when human bodies collide, they don't just bounce off of each other. This "inelastic" collision results in the transfer of kinetic energy being absorbed by bones, tissues and organs. The player with the least stored energy will suffer the most damage from the hit, especially if that player has less "body cushion" to absorb the impact.

To calculate your own real world energy loss scenario, visit the Exploratorium's "Science of Hockey" calculator. For both Sutter and Kostitsyn, they received checks from players who outweighed them by 20 pounds and were skating faster.

The average mass and acceleration variables are also growing as today's NHL players are getting bigger and faster. In a study released in September, Art Quinney and colleagues at the University of Alberta tracked the physiological changes of a single NHL team over 26 years, representing 703 players. Not surprisingly, they found that defensemen are now taller and heavier with higher aerobic capacity while forwards were younger and faster. Goaltenders were actually smaller with less body mass but had better flexibility. However, the increase in physical size and fitness did not correspond with team success on the ice. But the checks sure hurt a lot more now.

Please visit my other articles on Livescience.com