Whether it's for money, marbles or chalk, the brains of reward-driven people keep their game faces on, helping them win at every step of the way. Surprisingly, they win most often when there is no reward. That's the finding of neuroscientists at Washington University in St. Louis, who tested 31 randomly selected subjects with word games, some of which had monetary rewards of either 25 or 75 cents per correct answer, others of which had no money attached.

Subjects were given a short list of five words to memorize in a matter of seconds, then a 3.5-second interval or pause, then a few seconds to respond to a solitary word that either had been on the list or had not. Test performance had no consequence in some trials, but in others, a computer graded the responses, providing an opportunity to win either 25 cent or 75 cents for quick and accurate answers. Even during these periods, subjects were sometimes alerted that their performance would not be rewarded on that trial.

Prior to testing, subjects were submitted to a battery of personality tests that rated their degree of competitiveness and their sensitivity to monetary rewards.

Designed to test the hypothesis that excitement in the brains of the most monetary-reward-sensitive subjects would slacken during trials that did not pay, the study is co-authored by Koji Jimura, PhD, a post-doctoral researcher, and Todd Braver, PhD, a professor, both based in psychology in Arts & Sciences. Braver is also a member of the neuroscience program and radiology department in the university's School of Medicine.

But the researchers found a paradoxical result: the performance of the most reward-driven individuals was actually most improved -- relative to the less reward-driven -- in the trials that paid nothing, not the ones in which there was money at stake.

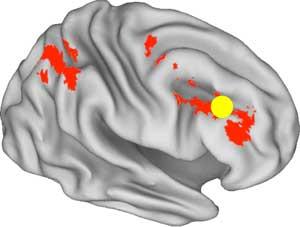

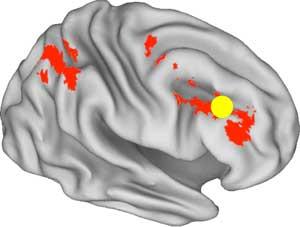

Even more striking was that the brain scans taken using functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) showed a change in the pattern of activity during the non-rewarded trials within the lateral prefrontal cortex (PFC), located right behind the outer corner of the eyebrow, an area that is strongly linked to intelligence, goal-driven behavior and cognitive strategies. The change in lateral PFC activity was statistically linked to the extra behavioral benefits observed in the reward-driven individuals.

The researchers suggest that this change in lateral PFC activity patterns represents a flexible shift in response to the motivational importance of the task, translating this into a superior task strategy that the researchers term "proactive cognitive control." In other words, once the rewarding motivational context is established in the brain indicating there is a goal-driven contest at hand, the brain actually rallies its neuronal troops and readies itself for the next trial, whether it's for money or not.

|

The brain's lateral prefrontal cortex (in yellow) shows heightened

and long-lasting activity in people more driven by rewards,

even when a reward is not offered. (Credit: Koji Jimura) |

"It sounds reasonable now, but when I happened upon this result, I couldn't believe it because we expected the opposite results," says Jimura, first author of the paper. "I had to analyze the data thoroughly to persuade myself. The important finding of our study is that the brains of these reward- sensitive individuals do not respond to the reward information on individual trials. Instead, it shows that they have persistent motivation, even in the absence of a reward. You'd think you'd have to reward them on every trial to do well. But it seems that their brains recognized the rewarding motivational context that carried over across all the trials."

The finding sheds more light on the workings of the lateral PFC and provides potential behavioral clues about personality, motivation, goals and cognitive strategies. The research has important implications for understanding the nature of persistent motivation, how the brain creates such states, and why some people seem to be able to use motivation more effectively than others. By understanding the brain circuitry involved, it might be possible to create motivational situations that are more effective for all individuals, not just the most reward-driven ones, or to develop drug therapies for individuals that suffer from chronic motivational problems.

Their

results are published April 26 in the early online edition of the

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Everyone knows of competitive people who have to win, whether in a game of HORSE, golf or the office NCAA basketball tournament pool. The findings might tell researchers something about the competitive drive.

The researchers are interested in the signaling chain that ignites the prefrontal cortex when it acts on reward-driven impulses, and they speculate that the brain chemical dopamine could be involved. That could be a potential direction of future studies. Dopamine neurons, once thought to be involved in a host of pleasurable situations, but now considered more of learning or predictive signal, might respond to cues that let the lateral PFC know that it's in for something good. This signal might help to keep information about the goals, rules or best strategies for the task active in mind to increase the chances of obtaining the desired outcome.

In the context of this study, when a 75-cent reward is available for a trial, the dopamine-releasing neurons could be sending signals to the lateral PFC that "jump start" it to do the right procedures to get a reward.

"It would be like the dopamine neurons recognize a cup of Ben and Jerry's ice cream, and tell the lateral PFC the right action strategy to get the reward -- to grab a spoon and bring the ice cream to your mouth," says Braver. "We think that the dopamine neurons fires to the cue rather than the reward itself, especially after the brain learns the relationship between the two. We'd like to explore that some more."

They also are interested in the "reward carryover state," or the proactive cognitive strategy that keeps the brain excited even in gaps, such as pauses between trials or trials without rewards. They might consider a study in which rewards are far fewer.

"It's possible we'd see more slackers with less rewards," Braver says. "That might have an effect on the reward carryover state. There are a host of interesting further questions that this work brings up which we plan to pursue."

Source:

Washington University in St. Louis

See also:

The Big Mo' - Momentum In Sports and

Tiger's Brain Is Bigger Than Ours