|

Thomas Talavage, co-director of the Purdue MRI Facility,

prepares to test a Jefferson High School football player.

(Credit: Purdue University photo/Andrew Hancock) |

A study by researchers at Purdue University suggests that some high school football players suffer undiagnosed changes in brain function and continue playing even though they are impaired.

"Our key finding is a previously undiscovered category of cognitive impairment," said Thomas Talavage, an expert in functional neuroimaging who is an associate professor of biomedical engineering and electrical and computer engineering and co-director of the Purdue MRI Facility.

The findings represent a dilemma because they suggest athletes may suffer a form of injury that is difficult to diagnose.

"The problem is that the usual clinical signs of a head injury are not present," said Larry Leverenz, an expert in athletic training and a clinical professor of health and kinesiology. "There is no sign or symptom that would indicate a need to pull these players out of a practice or game, so they just keep getting hit."

Findings are detailed in a research paper appearing online this week in the

Journal of Neurotrauma.

The team of researchers screened and monitored 21 players at Jefferson High School in Lafayette, Ind.

"The athletes wore helmets equipped with six sensors called accelerometers, which relay data wirelessly to equipment on the sidelines during each play," said Eric Nauman, an associate professor of mechanical engineering and an expert in central nervous system and musculoskeletal trauma.

Impact data from each player were compared with brain-imaging scans and cognitive tests performed before, during and after the season. The researchers also shot video of each play to record and study how the athletes sustained impacts.

Whereas previous research studying football-related head trauma has focused on players diagnosed with concussions, the Purdue researchers tested all of the players. They were surprised to find cognitive impairment in players who hadn't been diagnosed with concussions.

The research team identified 11 players who either were diagnosed by a physician as having a concussion, received an unusually high number of impacts to the head or received an unusually hard impact. Of those 11 players, three were diagnosed with concussions during the course of the season, four showed no changes and four showed changes in brain function.

"So half of the players who appeared to be uninjured still showed changes in brain function," Leverenz said. "These four players showed significant brain deficits. Technically, we aren't calling the impairment concussions because that term implies very specific clinical symptoms, such as losing consciousness or having trouble walking and speaking. At the same time, our data clearly indicate significant impairment."

The findings support anecdotal evidence that football players not diagnosed with concussions often seem to suffer cognitive impairment.

Researchers evaluated players using a GE Healthcare Signa HDx 3.0T MRI to conduct a type of brain imaging called functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI, along with a computer-based neurocognitive screening test.

"We're proud of our association with Purdue and feel longitudinal studies will provide a valuable platform to better study brain injuries," said Jonathan A. Murray, general manager of cross business programs for GE Healthcare.

The research could aid efforts to develop more sensitive and accurate methods for detecting cognitive impairment and concussions; more accurately characterize and model cognitive deficits that result from head impacts; determine the cellular basis for cognitive deficits after a single impact or repeated impacts; and develop new interventions to reduce the risk and effects of head impacts.

"By integrating the fMRI with head-based accelerometers and computer-based cognitive assessment, we are able to detect subtle levels of neurofunctional and neurophysiological change," Nauman said. "These data provide an opportunity to accurately track both the initial changes as well as the recovery in cognitive performance."

|

| (Credit: iStockphoto/Bill Grove |

The ongoing research may help to determine how many blows it takes to cause impairment, which could lead to safety guidelines on limiting the number of hits a player receives per week. "We're not yet sure exactly how many hits this is, but it's probably around 50 or 60 per week, which is not uncommon," Nauman said. "We've had kids who took 1,600 impacts during a season."

The research paper was written by Nauman, Leverenz, Talavage, Katie Morigaki, a graduate student in the Department of Health and Kinesiology, biomedical engineering graduate student Evan Breedlove, mechanical engineering graduate student Anne Dye, electrical and computer engineering graduate student Umit Yoruk, and Henry Feuer, a physician and neurosurgeon in the Department of Neurosurgery at the Indiana University School of Medicine.

Feuer is a neurosurgical consultant to the National Football League's Indianapolis Colts and a member of NFL subcommittees assessing the effects of mild traumatic brain injury.

The researchers studied the football players last season and are continuing the work this season.

The helmet-sensor data demonstrated that undiagnosed players who didn't show impairment received blows in many areas of the head, but the undiagnosed players who showed impairment received a large number of blows primarily to the top and front. This part of the brain is involved in "working memory," including visual working memory, a form of short-term memory for recalling shapes and visual arrangement of objects such as the placement of furniture in a room, Nauman said.

"These are kids who put their head down and take blow after blow to the top of the head," said Nauman, who also is an associate professor of biomedical engineering and basic medical sciences and leads Purdue's Human Injury Research and Regenerative Technologies Laboratory. "We've seen this primarily in linebackers and linemen, who tend to take most of the hits."

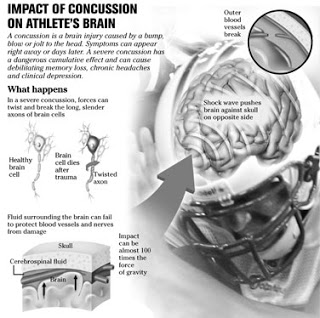

Helmet sensor data indicate impact forces to the head range from 20 to more than 100 Gs.

"To give you some perspective, a roller coaster subjects you to about 5 Gs and soccer players may experience up to 20 G accelerations from heading the ball," Nauman said.

Head impacts cause the brain to bounce back and forth inside the skull, damaging neurons or surrounding tissue. The trauma can either break nerve fibers called axons or impair signaling junctions between neurons called synapses.

The findings suggest the undiagnosed players suffer a different kind of brain injury than players who are diagnosed with a concussion.

"To be taken out of a game you have to show symptoms of neurological deficits -- unsteady balance, blurred vision, ringing in the ears, headaches and slurred speech," Leverenz said. "Unlike the diagnosed concussions, however, these injuries don't affect how you talk, whether you can walk a straight line or whether you know what day it is."

The fMRI reveals information about brain metabolism and blood flow, showing which parts of the brain are most active during specific tasks, Talavage said.

"One of the most challenging aspects of treating concussions is diagnosing the part of the brain that has been damaged," he said.

The fMRI data from before, during and after the season were compared to see whether there was any difference in brain activity that indicated impairment. The players also were studied using a standard cognitive test to show how well they were able to remember specific letters, words and patterns of lines.

The work may enable researchers to learn whether high school players accumulate damage over several seasons or whether they recover fully from season to season. The researchers have found that players diagnosed with concussions or who showed marked cognitive impairment had not yet recovered by the end of the season.

New preliminary data, however, suggests the players might recover before the start of the next season, but additional research is needed to determine the extent of recovery, Talavage said.

The work brings together faculty members from Purdue's College of Engineering and the new College of Health and Human Sciences along with research partners at GE Healthcare. The multidisciplinary team includes researchers specializing in neuroimaging, brain health, biomechanics, clinical sports medicine and analytical modeling.

The research group, called the Purdue Acute Neural Injury Consortium, also is studying ways to reduce traumatic brain injury in soldiers who suffer concussions caused by shock waves from explosions. "There are numerous parallels between head injuries experienced by soldiers and football players," Nauman said.

Other researchers in the consortium are Dennis A. Miller, a sports medicine expert; Charles A. Bouman, the Michael J. and Katherine R. Birck Professor of Electrical and Computer engineering and co-director of the Purdue MRI Facility; and Alexander L. Francis, an expert in learning and cognitive processing and an associate professor of speech, language and hearing sciences.

The work has been funded by the Indiana Department of Health and GE Healthcare. The researchers would like to extend their study to more high schools and are seeking additional funding for the work.

Researchers are working to create a helmet that reduces the cumulative effect of impacts, said John C. Hertig, executive director of the Alfred Mann Institute for Biomedical Development at Purdue.

"We're funding the development of a novel injury mitigation system created by researchers at Purdue for use in sports or military helmets," Hertig said. "This technology is targeted at mitigating the collective impacts absorbed by the brain in such a way as to dissipate the harmful energy that occurs during repeated impacts. Football linemen, soccer and hockey players, and others will benefit from the re-engineering of a sports helmet design created by Eric Nauman and his team."

Source:

Purdue University and Thomas M. Talavage, Eric Nauman, Evan L. Breedlove, Umit Yoruk, Anne E Dye, Katie Morigaki, Henry Feuer, Larry J. Leverenz.

Functionally-Detected Cognitive Impairment in High School Football Players Without Clinically-Diagnosed Concussion.

Journal of Neurotrauma, 2010; : 101001044014052 DOI:

10.1089/neu.2010.1512

See also: Hockey Hits Are Hurting More and Lifting The Fog Of Sports Concussions

"While the majority of concussions are self-limited injuries, catastrophic results can occur and we do not yet know the long-term effects of multiple concussions," said Jeffrey Kutcher, MD, MPH, chair of the AAN's Sports Neurology Section, which drafted the position statement. "We owe it to athletes to advocate for policy measures that promote high quality, safe care for those participating in contact sports."

"While the majority of concussions are self-limited injuries, catastrophic results can occur and we do not yet know the long-term effects of multiple concussions," said Jeffrey Kutcher, MD, MPH, chair of the AAN's Sports Neurology Section, which drafted the position statement. "We owe it to athletes to advocate for policy measures that promote high quality, safe care for those participating in contact sports." "While the majority of concussions are self-limited injuries, catastrophic results can occur and we do not yet know the long-term effects of multiple concussions," said Jeffrey Kutcher, MD, MPH, chair of the AAN's Sports Neurology Section, which drafted the position statement. "We owe it to athletes to advocate for policy measures that promote high quality, safe care for those participating in contact sports."

"While the majority of concussions are self-limited injuries, catastrophic results can occur and we do not yet know the long-term effects of multiple concussions," said Jeffrey Kutcher, MD, MPH, chair of the AAN's Sports Neurology Section, which drafted the position statement. "We owe it to athletes to advocate for policy measures that promote high quality, safe care for those participating in contact sports."