Of all of the decisions parents face regarding their children's future, choosing between shoulder pads or running shoes for their Christmas present seems trivial. Well, according to Kevin Reilly, president of

Atlas Sports Genetics, this is a decision you should not take lightly.

"If you wait until high school or college to find out if you have a good athlete on your hands, by then it will be too late," he said in a recent

New York Times interview. "We need to identify these kids from 1 and up, so we can give the parents some guidelines on where to go from there."

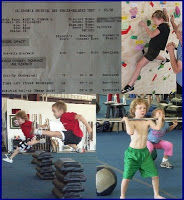

Earlier this month, Reilly's company began marketing a $149 saliva swab test for kids, aged 1 to 8, to determine which variant of the gene

ACTN3 is in their DNA. According to a

2003 Australian study, ACTN3 was shown to be a marker for two different types of athletic prowess, explosive power or long endurance. While everyone carries the gene, the combination of variants inherited, one from each parent, differs.

Science of success

The R variant of ACTN3 signals the body to produce a protein, alpha-actinin-3, which is found exclusively in fast-twitch muscles. The X variant prohibits this production. So, athletes inheriting two R variants may have a genetic advantage in sports requiring quick, powerful muscle contractions from their fast-twitch muscle fibers.

In the ACTN3 study,

Dr. Kathryn North and her lab at the Institute for Neuromuscular Research of the University of Sydney looked at 429 internationally ranked Australian athletes and found significant correlation between power sport athletes and the presence of the R variant. All of the female sprint athletes had at least one R variant, as did the male power-sport athletes. In fact, 50 percent of the 107 sprinters had two copies of the R variant.

What about those aspiring athletes that were not fortunate enough to inherit the R variant and its protein producing qualities?

North's team also noted that the elite endurance athletes seemed to be linked to the XX variation, although only significantly in the female sample. In 2007, her team pursued this link by developing a strain of mice that was completely deficient in the alpha-actinin-3 protein similar to an athlete with an XX allele. They found the muscle metabolism of the mice without the protein was more efficient. Amazingly, the mice were able to run 33 percent farther than mice with the normal ACTN3 gene.

Cloudy future

Additional research is showing mixed results, however.

In 2007, South African researchers found no significant correlation between 457 Ironman triathletes, known for their endurance, and the XX combination. This year, Russian researchers at the St. Petersburg Research Institute of Physical Culture also failed to establish the XX-endurance performance link among 456 elite rowers but did find the RR connection among a sample of Russian power sports athletes.

So, can we at least find the next Usain Bolt among our kids?

"Everybody wants to predict future athletic success based on present achievement or physical makeup. But predicting success is much more difficult than most people think," Robert Singer, professor and chair of the department of exercise and sport sciences at the University of Florida warns in the book "

Sports Talent" (Human Kinetics Publishers, 2001) by Jim Brown.

"There are too many variables, even if certain athletes have a combination of genes that favors long-range talent," Singer said. "A person's genetic makeup can be expressed in many different ways, depending on environmental and situational opportunities. Variables such as motivation, coachability, and opportunity can't be predicted."

Destiny?

Just as we assume that kids that are at the 99 percent percentile in height are destiny-bound for basketball or volleyball, having this peek into their genome may tempt parents to limit the sports choices for their son or daughter.

Even Mr. Reilly expressed his concern in the Times article: "I'm nervous about people who get back results that don't match their expectations," he said. "What will they do if their son would not be good at football? How will they mentally and emotionally deal with that?"

For those parents that are just not ready to discover the sports destiny of their child, or just want to save the $150, there is a much simpler alternative. Hold your son or daughter's hand, palm up. Measure the lengths of their index finger and their ring finger. Divide the former by the latter. According to John Manning, professor of psychology at the University of Central Lancashire, if the ratio is closer to .90 than 1.0, you may have a budding superstar.

Manning explains in his aptly named new book, "

The Finger Book" (Faber and Faber, 2008),that the amount of a fetus' exposure to testosterone in the womb determines the length of the ring finger, while estrogen levels are expressed in the length of the index finger. According to Manning's theory, more testosterone means more physical and motor skill ability.

The digit ratio theory, as it is known, has been the subject of more than 120 studies to find its effect on athletic, musical and even lovemaking aptitude.

Don't worry if the ratio is closer to 1.0, which is by far the norm. Plus, you will be able to relax, enjoy your kids' sports events and only worry about their genetic disposition to being happy.

Please visit my other articles on Livescience.com